This is a short story written by cyberpunk author Bruce Sterling, who is known for writing books such as The Hacker Crackdown to The Difference Engine (with William Gibson) to Schismatrix; in addition to writing the introduction to The Glass Bees by Ernst Jünger and We by Yevgeny Zamyatin. Remaining a relevant force of tech-realism in this ultra-modern utopia, Bruce has supplied cutting-edge commentary on the state of technology and surveillance to his followers and detractors alike. He has granted us permission to print this story of his in Trigger Warning, which was originally written in 2010.

So, I’m required to write this want-ad in order to get any help with my business. Only I have, like, a very bad trust rating on this system. I have rotten karma and an awful reputation. “Don’t even go there, don’t listen to a word he says: because this guy is pure poison.”

So, if that kind of crap is enough for you, then you should stop reading this right now.

However, somebody is gonna read this, no matter what. So let me just put it all out on the table. Yes, I’m a public enemy. Yes, I’m an ex-con. Yes, I’m mad, bad, and dangerous to link to.

But my life wasn’t always like this. Back in the good old days, when the world was still solid and not all termite-eaten like this, I used to be a well-to-do, well-respected guy.

Let me explain what went on in prison, because you’re probably pretty worried about that part.

First, I was a non-violent offender. That’s important. Second, I turned myself in to face “justice.” That shows that I knew resistance was useless. Also a big point on my side.

So, you would think that the maestros of the new order would cut me some slack in the karma ratings: but no. I’m never trusted. I was on the losing side of a socialist revolution. They didn’t call me a “political prisoner” of their “revolution,” but that’s sure what went on. If you don’t believe that, you won’t believe anything else I say, so I might as well say it flat-out.

So, this moldy jail I was in was this old dot-com McMansion, out in the Permanent Foreclosure Zone in the dead suburbs. That’s where they cooped us up. This gated community was built for some vanished rich people. That was their low-intensity prison for us rehab detainees.

As their rehab population, we were a so-called “resiliency commune.” This meant we were penniless, and we had to grow our own food, and also repair our own jail. Our clothes were unisex plastic orange jumpsuits. They had salvaged those somewhere. There had always been plenty of those.

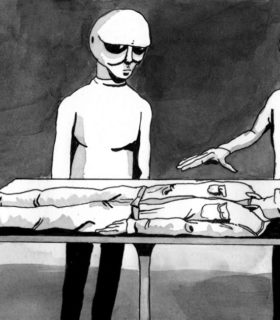

So we persisted out there as best we could, under videocam surveillance, with parole cuffs on our ankles. See, that was our life. Every week, our itchy, dirty column of detainees go to march thirteen miles into town, where our captors lived. We did hard-labor “community service” there with our brooms, shovels, picks, and hoes. We got shown off in public as a warning to others.

This place outside was a Beltway suburb before Washington was abandoned. The big hurricane ran right over it, and crushed it down pretty good, so now it was a big green hippie jungle. Our prison McMansion had termites, roaches, mold, and fleas, but it was once a nice house. This rambling wreck of a town was half storm-debris. All of the lawns were replaced with wet, weedy towering patches of bamboo, or marijuana—or hops, or kenaf, whatever (I never could tell those farm crops apart).

The same goes for the “garden roofs,” which were dirt piled on top of the dirty houses. There were smelly goats running loose, chickens cackling. Salvaged umbrellas and chairs toppled in the empty streets. No traffic signs, because there were no cars.

Sustainable Utopia is a densely crowded settlement full of people in poorly washed clothing who are hanging out making nice. Constant gossip—they call that “social interaction.” No sign of that one percent of the population that once owned half of America. The rich elite just blew it totally. They dropped their globalized ball. They panicked. So they’re in jail, like I was. Or they’re in exile somewhere, or else they jumped out of penthouses screaming when the hyperinflation ate them alive.

And boy, do I ever miss them. No more billboards, no more chain stores, no big-box Chinese depots and no neon fried-food shacks. It’s become another world, as in “another world is possible,” and we’re stuck in there. It’s very possible, very real, and it’s very smelly. There are constant power blackouts. Every once in a while, some armed platoon of “resilient nation-builder” militia types would come by on their rusty bicycles. Sometimes they brought shot-up victims on stretchers. The Liberated Socialist Masses were plucking their homemade banjos on rickety porches. Lots of liberty, equality, fraternity, solidarity, compost dirt, unshaved legs, and dense crowding.

Otherwise, the crickets chirp.

Those were, like, the lucky people who were outside our prison. Those cooperative people are the networked future.

So, my cellmate Claire was this forty-something career lobbyist who used to be my boss inside the Beltway. Clair was full of horror stories about the cruelty of the socialist regime. Because, in the old days before we got ourselves arrested, alarmist tales of this kind were Claire’s day-job. Claire peddled political spin to the LameStream Media to make sure that corporations stayed in command, so that situations like our present world stayed impossible.

Obviously, Claire was not that great at this strategy. Me, I was more of the geek technician in our effort. My job was to methodically spam and troll the sharing-networks. I would hack around with them, undermine them, and make their daily lives difficult. Threaten IP lawsuits. Spread some Fear, Uncertainty, and Doubt. Game their reputation systems. Gold-farm their alternative economies. Engage in DDOS attacks. Harass activist ringleaders with blistering personal insults. The usual.

Claire and I had lots of co-workers all up and down K-Street. Both seaboards, too, and all over Texas. Lavishly supported by rich-guy think-tanks, we were the covert operatives in support of an ailing system. We did that work because it paid great.

Personally, I loved to buy stuff: I admired a consumer society. I sincerely liked to carry out a clean, crisp, commercial transaction: the kind where you simply pay some money for goods and services. I liked driving my SUV to the mall, whipping out my alligator wallet, and buying myself some hard liquor, a steak dinner, and maybe a stripper. All that awful stuff at the Pottery Barn and Banana Republic where you never knew “Who the hell was buying that?” That guy was me.

Claire and I hated the sharing networks, because we were paid to hate them. We hated all social networks, like Facebook, because they destroyed the media that we owned. We certainly hated free software, because it was like some ever-growing anti-commercial fungus. We hated search engines and network aggregators, people like Google—not because Google was evil, but because they weren’t. We really hated “file-sharers”—the swarming pirates who were chewing up the wealth of our commercial sponsors.

We hated all networks on principle: we even hated power networks. Wind and solar only sort worked, and were very expensive. We despised green power networks because climate change was a myth. Until the climate actually changed. Then the honchos who paid us started drinking themselves to death.

If you want to see a truly changed world, then a brown sky really makes a great start. Back in the day, we could tell the public “Hey, the sky up there is still blue, who do you believe, me or your lying eyes?” And we tried that, but we ran out of time for it. After that tipping-point, our bottom-line economy was not “reality” at all. It was the myth.

My former life in mythland had suited me just great. Then I had no air conditioning. My world was wet, dirty, smelly, moldy, swarming with fleas, chiggers, bedbugs, and mosquitoes. Also, I was in prison. When myths implode, that’s what happens to good people.

So, Claire and I discussed our revenge. whenever we were out of earshot and oversight of the solar-powered prison webcams. Claire and I spent a lot of time on revenge fantasies, because that kept our morale up.

“Look, Bobby,” she told me, as she scratched graffiti in the wall with a ten-penny nail, “this rehab isn’t a proper ‘prison’ at all! This is a bullshit psychological operation intended to brainwash us. Leftists in power always do that! If they give you a fair trial, you can at least get a sentence and do time. If they claim you are crazy, they can sit on your neck forever!”

“Maybe we really are crazy now,” I said. “Having the sky change color can do that to people.”

“There’s only one way out of this Kumbaya nuthouse,” she said. “We gotta learn to talk the way they want to hear! So that’s our game plan from now on. We act very contrite, we do their bongo dance, whatever. Then they let us out of this gulag. After that, we can take some steps.”

Claire was big on emigrating from the USA. Claire somehow imagined there was some country in the world that didn’t have weather. The inconvenient laws of physics had never much appealed to Claire. We’d donated the laws of physics to our opponents by pretended that air wasn’t air. Now the long run of that tactic was splattered all around us. We had nothing left but worthless paper money and some Red State churches half-full of creationists.

We had gone bust. We had suffered a vast, Confederate-style defeat. The economy was Gone with the Wind, and everybody was gonna stay poor, angry, and dirt-stupid for the next century.

So: when we weren’t planting beans in the former back yard, or digging mold out of the attic insulation, we had to do rehab therapy. This was our prisoner consciousness-building encounter scheme. The regime made us play social games. We weren’t allowed computer games in prison: just dice, graph paper, and some charcoal sticks we made ourselves.

So we played this elaborate game called “Dungeons and Decency.” Three times a week. The lady warden was our dungeon master.

This prison game was diabolical. It was very entertaining, and compulsively playable. This game had been designed by left-wing interaction designers, the kind of creeps who built no-for-profit empires like Wikipedia. Except they’d designed it for losers like us.

Everybody in rehab had to role-play. We had to build ourselves another identity, because this new pretend-identity was supposed to help us escape the stifling spiritual limits of our previous, unliberated, greedy individualist identities.

In this game, I played an evil dwarf. With an axe. Which would have been okay, because that identity was pretty much me all along. Except that the game’s reward system had been jiggered to reward elaborate acts of social collaboration. Of course we wanted to do raids and looting and cool fantasy fighting, but that wasn’t on. We were very firmly judged on the way we played this rehab game. It was never about grabbing the gold, it was all about forming trust coalitions so as to collectively readjust our fantasy infrastructure.

This effort went on endlessly. We played it for ages. We kept demanding to be let out, they kept claiming we didn’t get it yet. The prison food got a little better. The weather continued pretty bad. We started getting charity packages. Once some folk singers came by and played us some old Johnny Cash songs. Otherwise, the gaming was pretty much it.

A whole lot was resting on this interactive Dungeons game. If you did great, they gave you some meat and maybe a parole hearing. If you blew it off, you were required to donate blood into the socialized health-care system. Believe you me, when they tap you more than a couple times, on a diet of homegrown cabbage? You start feeling mighty peaked.

Yeah, it got worse. Because we had to cooperate with other teams of fantasy game players in other prisons. These other convicts rated our game performance, while we were required to rate them. We got to see the highlights of their interactions on webcams—(we prisoners were always on webcams).

We were supposed to rate these convicts on how well they were sloughing off their selfish ways, and learning to integrate themselves into a spiritualized, share-centric, enlightened society. Pretty much like Alcoholics Anonymous, but without God or the booze.

Worse yet, this scheme was functioning. Some of our cellmates, especially the meek, dorky, geeky ones, were quickly released. The wretches strung out on dope were pretty likely to manage in the new order, too. They’d given up jailing people for that.

This degeneration had to be stopped somehow. Since I had been a professional troll, I was great at gaming. I kept inventing ways to hack the gaming system and get people to fight. This was the one thing inside the prison that recalled the power I’d once held in my old life.

So, I threw myself into that therapy heart and soul. I worked my way up to the fifteenth level Evil Dwarf. I was the envy of the whole prison system, a living legend. I got myself some prison tattoos, made a shiv …. Maybe I had a bleak future, stuck inside the joint, but I still had integrity! I had defied their system! I could vote down the stool-pigeons and boost the stand-up guys who were holding out against the screws.

I was doing great at that, really into it, indomitable—until Claire told me that my success was queering her chances of release. They didn’t care what I did inside the fantasy game. All the time, I was really being judged on my abuse of the ratings system. Because they knew what I was up to. It was all a psychological trap! The whole scheme was their anti-hacker honeypot. I had fallen into it like the veriest newbie schmoe!

You see, they were scanning us all the time. Nobody ever gets it about the tremendous power of network surveillance. That’s how they ruled the world though: by valuing every interaction, by counting every click. Every time one termite touched the feelers of another termite, they were adding that up. In a database.

Everybody was broke: extremely poor, like pre-industrial hard-scrabble poor, very modest, very “green.” But still surviving. The one reason we weren’t all chewing each other’s cannibal thighbones (like the people on certain more disadvantaged continents) was because they’d stapled together this survival regime out of socialist software. It was very social. Ultra-social. No “privatization,” no “private sector,” and no “privacy.”

They pretended that it was all about happiness and kindliness and free-spirited cooperation and gay rainbow banners and all that. It was really a system that was firmly based on “social capital.” Everything social was your only wealth. In a real “gift economy,” you were the gift. You were living by your karma. Instead of a good old hundred-dollar bill, you just had a virtual facebooky thing with your own smiling picture on it, and that picture meant “Please Invest in the Bank of Me!”

That was their New Deal. One big game of socially approved activities. For instance: reading Henry David Thoreau. I did that. I kinda had to. I had this yellow, crumbly, prison edition of a public-domain version of Walden.

Man, I hated that Thoreau guy. I wanted to smack Mr. Nonviolent Moral Resistance right across his chops. I did learn something valuable from him, though. This communard Transcendental thing that had us by the neck? The homemade beans, the funky shacks, the passive-aggressive peacenik dropout thing? That was not something that had invaded America from Mars. That was part of us. It had been there all along. Their New Age spiritual practice was America’s dark freaky undercurrent. It was like witchcraft in the Catholic Church.

Now these organized network freaks had taken over the hurricane wreck of the church. They were sacrificing goats in there, and having group sex under their hammer and sickle while witches read Tarot cards to the beat of techno music.

These Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability geeks were maybe seven percent of America’s population. But the termite people had seized power. They were the Last Best Hope of a society on the skids. They owned all the hope because they had always been the ones who knew our civilization was hopeless. So, I was in their prison until I got my head around that new reality. And I realized that this was inevitable. That it was the way forward. I loved Little Brother. After that, I could go walkies.

That was the secret. All the rest of it: the natural turmoil of the period… the swarms of IEDS, and the little flying bomb drones, and the wiretaps, and the lynch mobs, and the incinerators, and the “regrettable excesses,” as they liked to call them—those were not the big story. That was like the exciting sci-fi post-apocalypse part that basically meant nothing that mattered.

Everybody wants the cool post-disaster story—the awesome part where you take over whole abandoned towns, and have sex with cool punk girls in leather rags who have sawed-off shotguns. Boy, I could only wish. In Sustainable-Land, did we have a cool, wild, survivalist lifestyle like that? No way. We had, like, night-soil buckets and vegetarian okra casseroles.

The big story was all about a huge, doomed society that had wrecked itself so thoroughly that its junkyard was inherited by hippies. The epic tale of the Soviet Union, basically. Same thing, different verse. Only more so.

Well, I could survive in that world. I could make it through that. People can survive a Reconstuction: if they keep their noses clean and don’t drink themselves to death. The compost heap had turned over. All the magic mushrooms came out of the dark. So they were on top, for a while. So what?

So, I learned to sit still and read a lot. Because that look like innocent behavior. When all the hippie grannies are watching you over their HAL 9000 monitors, poring over your every activity like Vegas croupiers with their zoom and slo-mo, then quietly reading paper books looks great. That’s the major consolation of philosophy.

So, in prison, I read, like Jean-Paul Sartre (who was still under copyright, so I reckon they stole his work). I learned some things from him. That changed me. “Hell is other people.” That is the sinister side of a social-software shared society, that people suck, that hell is other people. Sharing with people is hell. When you share, then no matter how much money you have, they just won’t leave you alone.

I quoted Jean-Paul Sartre to the parole board. A very serious left-wing philosopher: lots of girlfriends (even feminists) he ate speed all the time, he hung out with Maoists. Except for the Maoist part, Jean Paul Sartre is my guru. My life today is all about my Existential authenticity. Because I’m a dissident in this society. Maybe I’m getting old-fashioned, but I’ll never go away. I’ll never believe what the majority says it believes. And I won’t do you the favor of dying young, either.

Because the inconvenient truth is that, authentically, about fifteen percent of everybody is no good. We are the nogoodniks. That’s one thing the Right knows, that the Left never understands: that, although fifteen percent of people are saintly and liberal bleeding hearts, and you could play poker with them blindfolded, another fifteen are like me. I’m a troll. I’m a griefer. I’m in it for me, folks. I need to “collaborate” or “share” the way I need to eat a bale of hay and moo.

Well, like I said to the parole board: “So what are you going to do to me? Ideally, you keep me tied up and you preach at me. Then I become your hypocrite. I’m still a dropout. You don’t convince me.

I can tell you what finally happened to me. I got off. I never expected that, couldn’t predict it, it came out of nowhere. Yet another world was possible I guess. It’s always like that.

There was a nasty piece of work up in the hills with some “social bandits.” Robin Hood is a cool guy for the peace and justice contingent, until he starts robbing the social networks, instead of the Sheriff of Nottingham. Robin goes where the money is—until there’s no money. Then, Robin goes where the food is.

So, Robin and his Merry Band had a face-off with my captors. That got pretty ugly, because social networks versus bandit mafias is like Ninjas Versus Pirates: it’s a counterculture fight to the finish.

However, my geeks had the technology, while redneck Robin just had his terrorist bows and arrows and the suits of Lincoln green. So, he fought the law and the law won. Eventually.

That fight was always a much bigger deal than I was. As dangerous criminals go, a keyboard-tapping troll like me was small potatoes compared to the redneck hillbilly mujihadeen.

So the European Red Cross happened to show up during that episode (because they like gunfire). The Europeans are all prissy about the situation, of course. They are like “What’s with these illegal detainees in orange jumpsuits, and how come they don’t have proper medical care?”

So, I finally get paroled. I get amnestied. Not my pal Claire, unfortunately for her. Claire and our female warden had some kind of personal difficulty, because they’d been college roommates or something—like, maybe some stolen boyfriend trouble. Something very girly and tenderly personal, all like that—but in a network society, the power is all personal. “The personal is political.” You mess with the tender feelings of a network maven, and she’s not an objective bureaucrat following the rule of law. She’s more like “To the Bastille with this subhuman irritation!”

Claire was all super-upset to see that I got my walking papers while she was heading for the gulag’s deepest darkest inner circles. Claire was like: “Bobby, wait, I thought you and I were gonna watch each other’s backs!” And I’m like, “Girlfriend, if it were only a matter of money, I would go bail for you. But I got no money. Nobody does. So, hasta luego. I’m on my own.”

So at last, I was out of the nest. And I needed a job. In a social network society, they don’t have any jobs. Instead, you have to invent public-spirited network-y things to do in public. If people really like what you do for “the commons,” then you get all kinds of respect and juice. They make nice to you. They suck up to you all the time, with potluck suppers, and they redecorate your loft. And I really hated that. I still hate it. I’ll always hate it.

I’m not a make-nice, live-in-the-hive kind of guy. However, even in a very densely networked society, there are some useful guys that you don’t want to see very much. They’ve very convenient members of society, crucial even, but they’re just not sociable. You don’t want to hang around with them, you don’t want to give them backrubs, follow their livestream, none of that. Society’s antisocial guys.

There’s the hangman. No matter how much justice he dishes out, the hangman is never a popular guy. There’s the gravedigger. The locals sure had plenty of work for him, so that job was already taken.

Then there was the exterminator. The man who kills bugs. Me. In a messed-up climate, there are a whole lotta bugs. Zillions of them. You get those big empty suburbs, the burnt-out skyscrapers, lotta wreckage, junk, constant storms, and no air conditioning? Smorgasbord for roaches and silverfish.

Tear up the lawns and grow survival gardens and you are gonna get a whole lot of the nastiness the lefties call “biodiversity.” Vast, swarming mobs of six-legged vermin. And endless, fertile, booming supply.

Mosquitoes carry malaria, fleas carry typhus. Malaria and typhus are never popular, even in the greenest, most tree-huggy societies.

So I found myself a career. A good career. Killing bugs. Megatons of them.

My major challenge is the termites. Because they are the best-organized. Termites are fascinating. Termites are not just pale little white-ants that you can crush with your thumb. The individual termites, sure they are, but a nest of termites is a network society. They share everything. They bore a zillion silent holes through seemingly solid wood. They have nurses, engineers, a whole social system. They run off fungus inside their guts. It’s amazing how sophisticated they are. I learn something new about them every day.

And, I kill them. I’m on call all the time, to kill termites. I got all the termite business I can possibly handle. I figure I can combat those swarmy little pests until I get old and gray. I stink of poison constantly, and I wear mostly plastic, and I’m in a breathing mask like Darth Vader, but I am gonna be a very useful, highly esteemed member of this society.

There will still be some people like me when this whole society goes kaput. And someday, it surely will. Because no Utopia ever lasts. Except for the termites, who’ve been at it since the Triassic period.

So, that is my story. This is my want-ad. It’s all done now, except for the last part. That’s your part: the important part where you yourself can contribute.

I need a termite intern. It’s steady work and lots of it. And now, because I wrote this all for you, you know what kind of guy you are pitching in with.

I know that you’re out there somewhere. Because I’m not the only guy around like me. If you got this far, you’re gonna send me email and a personal profile.

It would help a lot if you were a single female, twenty-five to thirty-five, shapely, and a brunette.

[Read on Shareable here.]

Bruce Sterling is an American science fiction author known for various novels and anthologies. His work has been a major force in defining the cyberpunk literary genre.